Polar bears inhabit the Arctic region across 19 subpopulations, including areas in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Norway, and Russia. These majestic creatures prefer the edges of pack ice where currents and wind interact, creating a dynamic environment of melting and refreezing that forms ice patches and leads, which are open spaces in the sea between sea ice.

1. Polar bears are travelers

Throughout the year, as sea ice advances and retreats, polar bears travel extensively to find food in the openings of the sea. Unlike other large carnivores, polar bears do not have fixed territories due to their dependence on sea ice. A young polar bear may travel over 1,000 km (600 miles) to establish its own home range, separate from its mother’s.

Scientists have tracked polar bears with home ranges spanning hundreds of miles. One satellite-tracked bear had a home range of nearly 5,000 km (3,100 miles), stretching from Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay to Greenland, then back to Ellesmere Island in Canada, before returning to Greenland.

2. Adapting to cold is a polar bear talent

Scientists believe that polar bears evolved from a common ancestor of the brown bear between 350,000 and 6 million years ago. As they moved north, the ancestors of modern polar bears had to adapt to cold conditions.

Polar bears have dense, insulating underfur topped by guard hairs of varying lengths. This fur is so effective at insulation that it prevents nearly all heat loss, making adult males susceptible to overheating when they run.

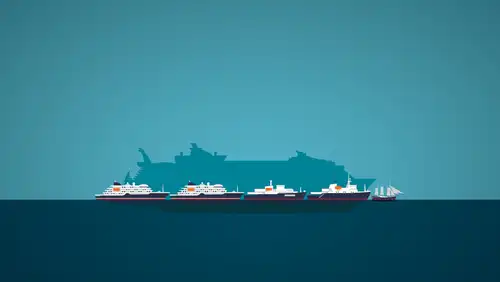

Travelers lucky enough to see them during Arctic cruises usually spot them walking at a conservative pace of around 5 kph (3 mph).

3. Polar bear fur is not actually white

Each polar bear hair shaft is pigment-free and transparent, with a hollow core that disperses and reflects light. Polar bears appear pure white when clean and in high-angle sunlight, especially after molting, which usually happens in spring and finishes by late summer. Before molting, accumulated oils from their seal diet can make them look yellow.

Underneath their fur, polar bears have warm black skin over a thick layer of fat, which can be up to nearly 11.5 cm (4.5 inches) thick. This fat layer is crucial for staying warm in the water, as wet fur is a poor insulator.

4. Polar bears know how to tread lightly

Polar bears are adept at moving around the Arctic without slipping on or crashing through thin ice. Their paws, which can be up to 30 cm (12 inches) across, help them tread on ice by allowing the bear to extend its legs far apart and lower its body to evenly distribute its weight. The footpads on the bottom of each paw are covered in small, soft bumps called papillae, which help the polar bear grip the ice and avoid slipping.

Their claws, each measuring more than 5 cm in length (2 inches), also aid in walking across the ice by gripping the slippery surface. This ability allows polar bears to reach speeds of up to 40 kph (25 mph) on ice.

5. Seals make up the preferred polar bear diet

Polar bears spend much of their time hunting for food, but success is not guaranteed. Ringed and bearded seals are their preferred catch to maintain their thick layer of fat. When in a fit and healthy state, polar bears may only eat the seal’s blubber and skin, leaving the carcass for scavengers like Arctic foxes, ravens, and other bears. While polar bears do not exclusively feed on seals, they are their most ideal nutrient source.

6. Polar bears prioritize their cubs

Pregnant polar bears need to eat a lot over the summer and autumn to build up enough fat reserves to survive the denning period. During October and November, the female bear seeks out maternity dens, usually on land where snow accumulates, such as coastal bluffs, river banks, or pressure ridges on the sea ice.

The polar bear typically gives birth to cubs weighing less than 1 kg (around 1 – 2 pounds) between November and January. She then nurses them until they are about 9 – 13 kg (20 – 30 pounds) before emerging from the den in March/April. The cubs remain with their mothers for about two years. Over a female’s lifetime, she can have five litters, one of the lowest reproductive rates of any mammal.

7. It takes a lot of sleep to sustain a polar bear

Scientists have recorded life from the polar bear perspective using collar cameras, providing insights into how polar bears in seasonal ice areas – where the sea ice melts completely in summer – spend their time and energy when forced to live on land. These recordings, combined with data from an accelerometer that measures changes in motion, reveal what polar bears do on land and how many calories they expend.

The data shows that polar bears spend about 78 percent of their time resting, 8 percent eating berries, 4 percent walking, and 10 percent on other activities like drinking and grooming. Polar bears are most active in the morning, between 7am and midday, and least active in the early evenings, from 5pm to 8pm.

8. DNA can be taken from a polar bear footprint

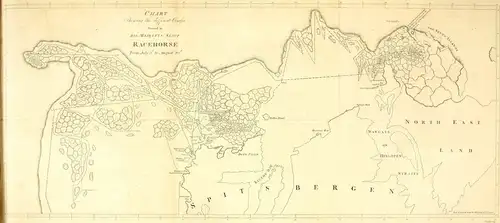

Researchers have managed to isolate polar bear DNA by collecting two scoops of snow from a polar bear footprint during an expedition to Svalbard. This Arctic archipelago has one of the world’s densest populations of polar bears.

A DNA specialist analyzed the sample and found that the polar bear’s last meal was a seal and a gull that were eaten after death. This method of studying polar bears is a significant advancement, as it is less intrusive than traditional tracking methods.

Related Trips

Blog

Hondius Photography and Video Workshops

Penguins, Petrels, and Prions: Top Antarctica Bird Tour Spots

The Arctic’s Most Phenomenal Fjords

Hot Ice: Breeding Practices of Five Polar Animals

Polar bear feast

First to the North Pole: Five Failed but Brave Expeditions

South Georgia Whaling Stations

The Small but Social Commerson’s Dolphin

Inside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault

Antarctica’s first Marine Protected Area

Fierce and Feathered: the Skuas of Antarctica

Under the Greenland Ice Sheet

5 Misconceptions You Might Have About Greenland

A Day of Whale Watching in Antarctica

The Plants of Antarctica

Wreck Diving in Antarctica

The secrets of Antarctic seals revealed

Deception Island deceptively active

Polar Amore: 14 Wildlife Pics to Warm up Your Valentine’s Day

8 Days / 7 Nights

8 Days / 7 Nights