The marine ecosystem of the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) stretches from the Bellingshausen Sea to the northern tip of the peninsula. This region includes the Antarctic Sea Ice Zone, a highly productive area that supports large populations of marine mammals, birds, and Antarctic krill. One of the highlights of this region, which you can observe on a whale-spotting Antarctica cruise, is the humpback whale.

Identifying humpback whales: the hump helps

Humpback whales are easily recognizable by their small dorsal fin, distinct hump at the front, long flippers, and unique black-and-white pattern on their tail. They typically travel alone or in small pods of two or three whales. It is common for mothers to touch the fins of their young, which is believed to be a sign of affection.

The singing of humpback whales

Humpbacks are renowned for their beautiful, complex songs. These songs, composed of sequences of moans, howls, and cries, can last for hours. Interestingly, only the males sing. Scientists think these songs might be used to attract potential mates. Males can sing for hours and repeat their song multiple times. All males in a population sing the same song, although each population's song is different.

The songs evolve throughout the year, so they are never singing the same tune for too long. Humpback whale songs can travel long distances in the ocean, being heard up to 30 km (20 miles) away. Researchers have found that humpback whales typically produce sounds with an audio frequency between 80 and 4,000 hertz.

Humpback calves guzzling milk

A female humpback whale breeds every two to three years and carries its calf for about a year. The calf usually measures between 3—4.5 meters (10—15 feet) and weighs around 900 kg (one ton), while adult humpbacks reach between 11.5—15 meters (37.5—49.2 feet) and weigh up to 36,000 kg (79,000 pounds).

The calf is nursed for a year, and the mother’s milk is 45—60 percent fat. Humpback calves can consume 600 liters (158 gallons) of milk per day. Within the first year, calves double in length and continue to grow over the next 10 years.

The ocean-sized buffets of the humpback whale

Humpback whales are baleen whales, meaning they have between 270 and 400 fringed overlapping plates hanging down from each side of their upper jaws instead of teeth. These are called baleen plates, made of keratin, the same material as human hair and nails. The plates are black and about 76 cm (30 inches) long.

The whales primarily eat small fish, krill, and plankton. To feed, humpback whales take large gulps of water. Below their mouths are 12—36 throat grooves that expand to hold the water. Humpbacks then filter the water, expelling it through the two blowholes on their backs. They hunt and feed in the summer and fast during the mating season, relying on their blubber reserves to focus on migration and mating.

They are social hunters, using a unique technique called “bubble netting,” where groups of humpbacks use air bubbles to herd, corral, or disorient fish. They are large eaters, capable of consuming up to 1,360 kg (3,000 pounds) of food per day.

Counting humpbacks from the air

During the summer, scientists estimate that around 3,000 humpback whales inhabit the West Antarctic Peninsula. To determine this, they conducted a ship-based helicopter survey of the whales and a net trawl survey for krill to see if the large population is linked to specific krill species. Scientists then created distribution maps to predict the densities of humpback whales in the western part of the peninsula.

They found that in one summer alone, the estimated 3,000 humpbacks frequented the area. Regarding the connection between krill type and whale numbers, researchers found no clear relationship between the humpback whales and the presence of a particular krill species. The whales were present regardless of krill availability.

3D mapping humpback whale behavior

In another study, researchers monitored a large group of humpbacks in Wilhelmina Bay, along the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula. This group, comprising over 300 whales, had five whales per square kilometer (0.38 square miles), breaking the previous record of one whale per square kilometer.

Over six weeks, scientists observed humpback whales feasting on krill. The whales fed continuously for 12 to 14 hours before falling asleep on the sea's surface. This is no surprise, as krill fill the sea from the surface down to 300 meters (985 feet) below.

In addition to observing their feeding, scientists attached tags to humpback whales that stayed on for 24 hours, capturing data such as temperature, sound, and position. This allowed scientists to create a 3D map of the whales’ underwater activities with its own soundtrack. Researchers even managed to attach tags to sleeping whales at the surface. Even half-asleep humpbacks were too full to move when researchers approached in a small boat to place tags on their heads!

An underwater humpback recording studio

Scientists studying humpback singing in the Western Antarctic Peninsula attached tags to whales during the Southern Hemisphere late fall (May and June). The tags were attached for 24-hour periods to six whales in one year and eight whales the following year to record sound production and body orientation.

The results showed song chorusing present on all the tag acoustic records, with multiple whales actively singing. The data also indicated that the songs were surrounded by periods of social sound production, reflecting the amount of social activity in the feeding grounds where the whales were tagged.

Humpback YouTube stars

Recently, a group of scientists attached temporary satellite tags and video cameras to humpback whales in the western part of the Antarctic Peninsula. These devices track the humpback’s movements and capture video images of everything in front of the whale for 24-48 hours before detaching and floating to the surface. Scientists then use GPS trackers to recover the tags and upload the videos. They have already captured unseen glimpses of humpback whales feeding, diving deep, and interacting with one another far below the sea's surface.

Blog

True South: A New Flag for a Global Antarctica

Coming Back from the Brink: The Fur Seals of Antarctica

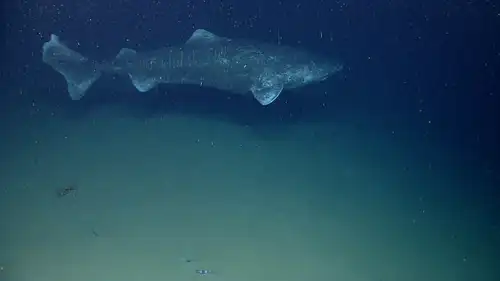

9 Facts about the Greenland Shark

Antarctica’s first Marine Protected Area

A Bug’s Life in Svalbard

What to Pack for Your Expedition Cruise to the Arctic or Antarctica

Birding Opportunities Abound in Spitsbergen

Weddell Sea: the Original Antarctic Adventure

The Small Mammals of the Arctic and Antarctica

Three Antarctica Cruise Deals

Tracking Greenland’s Wildlife from Space

Polar Cruises: The Ultimate Icebreaker

The Mysteries of the Beluga Whale

Peaks, Fjords, and Auroras: 14 East Greenland Attractions

Adélie Penguins: the Little People of the Antarctic

Polar Cuisine in Pictures

Five Birds You Might See on Your Greenland Cruise

Arctic vs. Antarctica: A Traveler’s Guide

Graham Land: A landscape dominated by volcanoes