There are only six species of seals that inhabit the Antarctic: Southern elephant seals, Antarctic fur seals, crabeater seals, leopard seals, Ross seals, and Weddell seals. While we are familiar with these species, much about their lives remains a mystery.

A different hunting pattern emerges

In a study on Antarctic fur seals, scientists and engineers from the British Antarctic Survey developed micro-global sensing loggers. These devices record times of local sunrise and sunset to estimate an animal’s location, capturing the winter feeding trips of over 100 female Antarctic fur seals, including eight individuals over multiple years from two significant breeding sites on the sub-Antarctic Bird Island and the South Atlantic Marion Island.

The study revealed that individual seals not only fed in different areas from each other within a winter but also changed their feeding locations between successive foraging trips. The scientists believe that food scarcity in winter forces these animals to broaden their search for sustenance.

When the data was analyzed over several years, a pattern emerged where these broader forages overlapped to some extent. This indicates that most seals revisited areas they had previously found to be productive and predictable.

The secret life of the leopard seals

One research project aimed to gain a rare insight into the underwater foraging ecology of leopard seals, a top predator in the Antarctic with razor-sharp canine teeth. Researchers at UC San Diego used Crittercams, small video cameras attached to the seals' bodies, to record their movements and uncover details about their hunting behavior, diet, and diving activities.

During 2013-2014, the project attached cameras to the backs of seven different leopard seals at Cape Shirreff, a remote location on Livingston Island in the Antarctic Peninsula. The cameras were attached after sedating the seals and were retrieved after 3-5 days without causing harm to the animals.

The project gathered over 50 hours of film footage, providing researchers with an unprecedented glimpse into the daily lives of these typically solitary seals. The footage revealed that, contrary to previous beliefs, the seals did not eat krill. Instead, they spent most of their time foraging along the seafloor for notothen fish, a bottom-dwelling ice fish species.

The leopard seals’ hunting expertise

Interestingly, the leopard seals had developed individualized techniques for hunting their prey. One female was observed swimming along the seafloor until she detected a fish hiding under a rock. She then flushed out the fish with her snout and caught it as it swam away, taking it to the surface to eat.

Prior to this study, only two out of over 30 scientific reports indicated that leopard seals ate bottom fish, and only one mentioned a diet that included notothen fish. The research also discovered that leopard seals engaged in food stealing. Contrary to the belief that they cooperated in feeding, the footage showed instances of fighting over food, with one video capturing a violent clash between two females over a fur seal pup.

Additionally, the seals were found to be scavenging carcasses, not randomly but by hoarding catches. They either defended their kill or hid it beneath rocks on the seafloor or at depths below 10 meters.

The Weddell seals’ large brain

One of the longest-standing research projects on any animal species is the Weddell seal study, ongoing since 1968. A few years ago, researchers from the National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center discovered that Weddell seal pups have proportionally the largest brains at birth of any known mammal.

Previous research indicated that Weddell seal pups face a steep learning curve, having to navigate beneath Antarctic sea ice alone as early as six weeks old. Scientists speculated that to learn this quickly, the pups must be born with advanced brains.

To investigate, scientists traveled to Antarctica to collect several seal pups and adults that had died of natural causes. The heads of the deceased seals were sent to the Smithsonian for examination. The research found that Weddell seal pups had brains that were, on average, 70 percent as large as adults, despite their small size, which is just 6-7 percent of an adult's body mass.

This finding aligns with other research suggesting that animals born into hostile environments tend to have larger brains at birth to help them survive. For example, zebras must be able to run with a herd just hours after birth. For Weddell seals, this means pups must be able to swim long distances under the sea ice, a dangerous task as they may struggle to find a hole in the ice or an air pocket in time to avoid drowning.

The energy required from the mother’s milk to support the pup’s brain development is enormous: of the 30-50 grams of glucose needed per day to survive, 28 grams are consumed by the brain.

Statistics of the elephant seals

Elephant seals are massive creatures, with males weighing up to 3,000 kilograms and adult females weighing between 300 and 900 kilograms before giving birth.

Recently, scientists from the University of Tasmania used modern tracking technology to follow the lives of nearly 300 southern elephant seals over six years. These seals were located in eight sites across the Southern Ocean, from Macquarie Island south of Australia to sub-Antarctic islands including South Georgia and the Kerguelen Islands. The seals spend more than 10 months of the year foraging at sea before returning to their breeding sites.

The scientists discovered some remarkable statistics, including individuals diving for up to 94 minutes to depths of almost 2,400 meters and the longest migration route reaching distances of 5,482 kilometers. The seals also provided invaluable information on the ocean, acting as mini-submarines recording ocean temperature and salinity wherever they traveled.

Blog

South Georgia in Spring

Baleen Whales – The Gentle Giants of the Ocean

Antarctic krill: Antarctica's Superfood

The First Buildings in Antarctica: Borchgrevink’s Historic Huts

Six Seal Species You Might See On Your Greenland Cruise

The Seven Best Things to Do in Antarctica

The Impact of Small vs. Large Cruise Ships

Eight Engaging Reindeer Facts

Birds of the North: 29 Arctic Birds and Seabirds

10 Illuminating Facts about the Northern Lights

Arctic on Foot: Hiking and Snowshoeing the Far North

The first race to the South Pole in 50 years

Greenland's History: When Vikings Ruled the Ice Age

The Giant Petrels of King George Island

Cruising Solo: The Benefits of Single-Passenger Polar Travel

Weddell Sea, Shackleton’s Endurance, and New Swabia

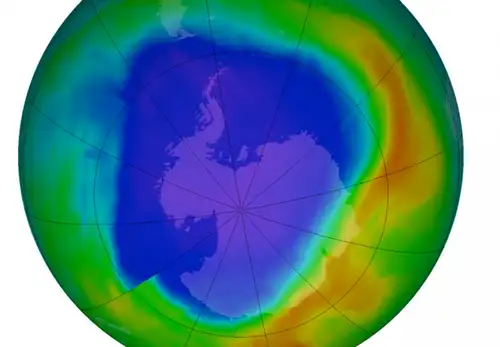

The ozone layer in Antarctica

The Evolving Shipboard Eco-traveler

Around Spitsbergen vs. North Spitsbergen