The South Orkney Islands are often overlooked as a destination for Antarctic travel.

However, they deserve attention: As part of the Scotia Sea Islands tundra ecoregion, the South Orkneys boast a rich array of wildlife despite their harsh environment.

This wildlife includes many iconic Antarctic animals: penguins, seals, seabirds, and whales.

(Although, due to extensive hunting, whales can be unfortunately rare in this area.)

While the South Orkney Islands host more than eleven species, the following list highlights some of the more popular ones, along with interesting facts about each.

1. Adélie penguins

Named after Adélie Land in Antarctica, claimed by the French, Adélie penguins are among the most recognizable penguins in the region.

Their genus name, Pygoscelis, translates to “rump-legged.”

Adélie penguins follow the sun around the Antarctic regions, as the winter sun never fully sets there. Some migrations have been as long as 17,600 km (10,900 miles).

They are one of only two penguin species found on the Antarctic mainland, the other being emperor penguins.

2. Gentoo penguins

The origin of the name “gentoo” for this penguin species is unclear, though it may derive from the Portuguese word gentio, meaning gentiles.

Gentoo penguins are the third largest penguin species globally.

Unlike other penguins, gentoos do not have an annual migration cycle, and their size increases the farther they live from the Antarctic Peninsula.

Gentoo penguins only breed in snow and ice-free areas, and cleanliness is crucial: If the previous year’s nesting site is too dirty or trampled, they will relocate.

They are the only penguin species in the Antarctic Peninsula region that is increasing in numbers and distribution.

3. Chinstrap penguins

Chinstrap penguins are known as “stonebreaker penguins” due to their piercing screech, which is said to break stones.

Outside the breeding season, they often gather on icebergs.

They are closely related to gentoo penguins, though their numbers are decreasing in the Antarctic Peninsula area.

Chinstrap penguins are one of the most aggressive penguin species and can lose half their weight during the breeding season.

4. Cape petrels

Cape petrels are the sole members of the Daption genus.

They share a trait with other Procellariidae family members, producing stomach oil that can be used for nourishment on long flights, regurgitated to feed their young, or sprayed at predators.

Daption comes from ancient Greek, meaning “little devourer,” and the “Cape pigeon” name comes from their habit of pecking at water while eating.

The “Cape” in their name refers to the Cape of Good Hope, where they were first identified.

Cape petrels are the only marine birds with distinct dappled coloring.

5. Snow petrels

Snow petrels are one of three bird species that breed exclusively in Antarctica and are the only members of the Pagodroma genus.

They have the southernmost breeding distribution of all birds.

Like many seabirds, snow petrels have a gland above their nasal passage that excretes a saline solution, helping them balance their salt intake from the sea.

The name “petrel” comes from Peter the Apostle, referencing the bird’s ability to “run” on water to take off.

Pagodroma is derived from the Greek words pagos, meaning “ice,” and dromos, meaning “a running course.”

6. Blue-eyed shags (Antarctic shags)

Often mistaken for imperial shags, blue-eyed shags are the only cormorants to venture into Antarctic regions.

They are the only Antarctic birds that maintain a nest year-round if the area is ice-free.

They don’t travel far from their nests to feed, historically making them a welcome sight for sailors, as their presence indicated nearby land.

Blue-eyed shags are the only Antarctic birds whose chicks are born without protective down, making them especially dependent on their parents for warmth.

The bumpy mound at the upper base of their bill is called a “caruncle.”

7. Antarctic fur seals

Unlike some other seal species, Antarctic fur seals have visible ears and are the only seals in the region with this feature.

They inhabit the Antarctic Convergence, a zone of water between the cold Antarctic waters and the more temperate waters to the north.

This species is one of nine fur seal species worldwide.

Antarctic fur seals can walk on land by turning their rear flippers forward, using them like feet.

Once nearly hunted to extinction, their numbers now reach hundreds of thousands (if not millions) during the breeding season.

8. Fin whales

Fin whales have an unusual asymmetry: The right side of their jaw, lip, and baleen are yellow-white, while the left sides are gray.

Being mostly pelagic, they are difficult for scientists to study.

They are the second largest mammals after blue whales.

Fin whales are nicknamed “razorbacks” due to a pronounced ridge behind their dorsal fins.

Their low-frequency sounds were initially mistaken for geological sounds, like tectonic plates grinding, as they are the lowest sounds of any animal, tied with the blue whale.

9. Sei whales

The name “sei” comes from the Norwegian word for pollock, a type of fish. Norwegians noticed that sei whales and pollocks often arrived in the same areas simultaneously each year.

Sei whales are compared to cheetahs because they can swim fast but tire quickly.

Like other baleen whales, they have two blowholes. However, unlike other baleens, sei whales prefer to stay out of truly cold waters.

Though they usually travel solo or in small pods, sei whales sometimes gather by the thousands in areas with abundant food.

Their Latin name, Balaenoptera borealis, means “winged whale” and “northern.”

10. Humpback whales

Barnacles on their bodies give humpback whales a bearded appearance.

They make long migrations twice a year: traveling to polar waters in the summer to feed and to tropical waters in the winter to breed.

Their Latin name, Megaptera novaeangliae, translates to “great winged newfoundlander,” referring to their large wing-like flippers.

A humpback’s song can be heard from almost 20 km (12 miles) away, and their spout can reach up to six meters (19.7 feet).

They arch their backs before making a deep dive, which is how they got their name.

11. Blue whales

If you’re fortunate, you might spot blue whales in the South Orkney Islands.

Growing up to 30 meters (98 feet) long and weighing up to 180 metric tons (395,000 pounds), blue whales are the largest creatures to have ever lived on Earth.

Their range is global, though they do not live under the polar ice caps.

Sadly, blue whales are still endangered due to extensive hunting.

Their main diet is krill, but they also consume other plankton. They are not aggressive towards humans and can be quite curious about ships.

Blue whale tongues can weigh more than elephants, and their hearts can weigh as much as cars.

Blog

10 Common Misconceptions About the Arctic

The History of Antarctica in Maps

Birds of the South: 33 Antarctic Birds and Seabirds

Danger Beneath the Water: 10 Facts About Leopard Seals

Greenlandic Inuit Beliefs

Weddell seals: The data collectors scientists of Antarctica

Ice streams and lakes under the Greenland Ice Sheet

Path of Polar Heroes: Hiking Shackleton’s Historic Route

The Norse Settlement of Greenland

10 Traits of Post-Ice-Age Greenland

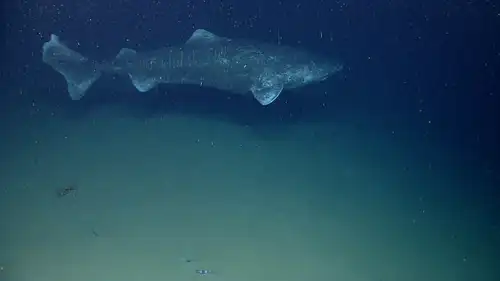

9 Facts about the Greenland Shark

What to Expect When Crossing the Drake Passage

Antarctic krill: Antarctica's Superfood

Polar Marine Visitors: the Whales of Antarctica and the Arctic

16 Conversation-Starting Svalbard Facts

Islands of the Blessed: Things to Do Around Cape Verde

Where the Polar Bears Roam

Eight Antarctic Misconceptions

12 Tips to Help Keep Birds Safe During an Antarctic Cruise