When it comes to polar exploration, the Arctic boasts a much longer history compared to Antarctica.

This isn't because the Arctic is inherently more appealing for travel than the southern polar regions. Rather, it's because people were already living within or near the Arctic Circle thousands of years before advancements in navigation, cartography, and ship-building made broader polar expeditions possible.

In fact, many parts of the Arctic had already been settled and fairly well mapped by the time Antarctica (known for centuries as Terra Australis and not even seen by human eyes until 1820) was confirmed to exist.

The three main epochs of ancient Arctic travel, spanning from Antiquity to the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, offer a captivating story filled with both sheer luck and brave intentions.

Pytheas and Thule: Ancient Greeks explore the Arctic

The earliest accounts of Arctic-bound travel in the ancient world date back to the era of Aristotle and Alexander the Great.

Geographer Pytheas embarked on a voyage north in 325 BCE (BC) to find the source of tin that occasionally reached his remote Greek colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille). He sailed past the Pillars of Hercules, the ancient name for the rocks of Gibraltar, and eventually circumnavigated the British Isles in his quest.

During these travels, he learned of a land even farther north called Thule, which he reportedly reached after another six days of sailing.

Pytheas described the sea of Thule as being curdled, which modern scholars believe meant frozen. The area Pytheas is said to have reached may have been the coast of Northern Norway or perhaps the Shetland Islands, which were part of ancient Thule.

It's uncertain whether Pytheas technically crossed over the Arctic Circle, but if he did, it would have likely been no farther north than Northern Norway.

Vikings and Pomors: Medieval Arctic travels

In the late 9th century, the Viking Naddod discovered Iceland. A few years later, another ancient Scandinavian, Gardar Svavarsson, saw the same island after losing his sailing route from Norway to the Faroes.

Gardar’s report of the area spurred a frenzy of colonization and was followed by at least one more happy accident: Gunnbjörn Ulfsson, another Norseman, got lost in a storm in either the late 800s or early 900s and apparently came within sight of the Greenland shoreline.

Seek and you shall find? Well, apparently not if you’re Norse.

Ulfsson’s sighting led to Erik the Red establishing a village on Greenland in 985. However, changing climates, such as those during the Little Ice Age, prevented these settlements from becoming more permanent, and they were all gone by around 1450.

But it wasn’t just lost Vikings who made discoveries in the medieval Arctic. Russians also played a significant role in far north exploration, as Pomors had been traveling areas of the northeast passage as far back as the 11th century.

By 1533, Russian monks had founded the Pechenga Monastery on the northern Kola Peninsula, from which Pomors explored Novaya Zemlya, the Barents Sea, and even Spitsbergen. Later, in 1648, the Cossack explorer Semyon Dezhnev became the first European to sail through the Bering Strait.

These developments were all leading toward the greatest era of world exploration in human history, just around the corner...

North by Northwest Passage: Renaissance men roam the Arctic

Within the span of about two hundred years, several European kingdoms engaged in an unprecedented movement of innovation, exploration, and colonization that would forever change the geography of the known world.

Known as the Age of Discovery, this Renaissance-era phenomenon was spurred by developments such as the 1409 translation of Ptolemy's Geographia into Latin, which introduced Western Europe to the concepts of longitude and latitude.

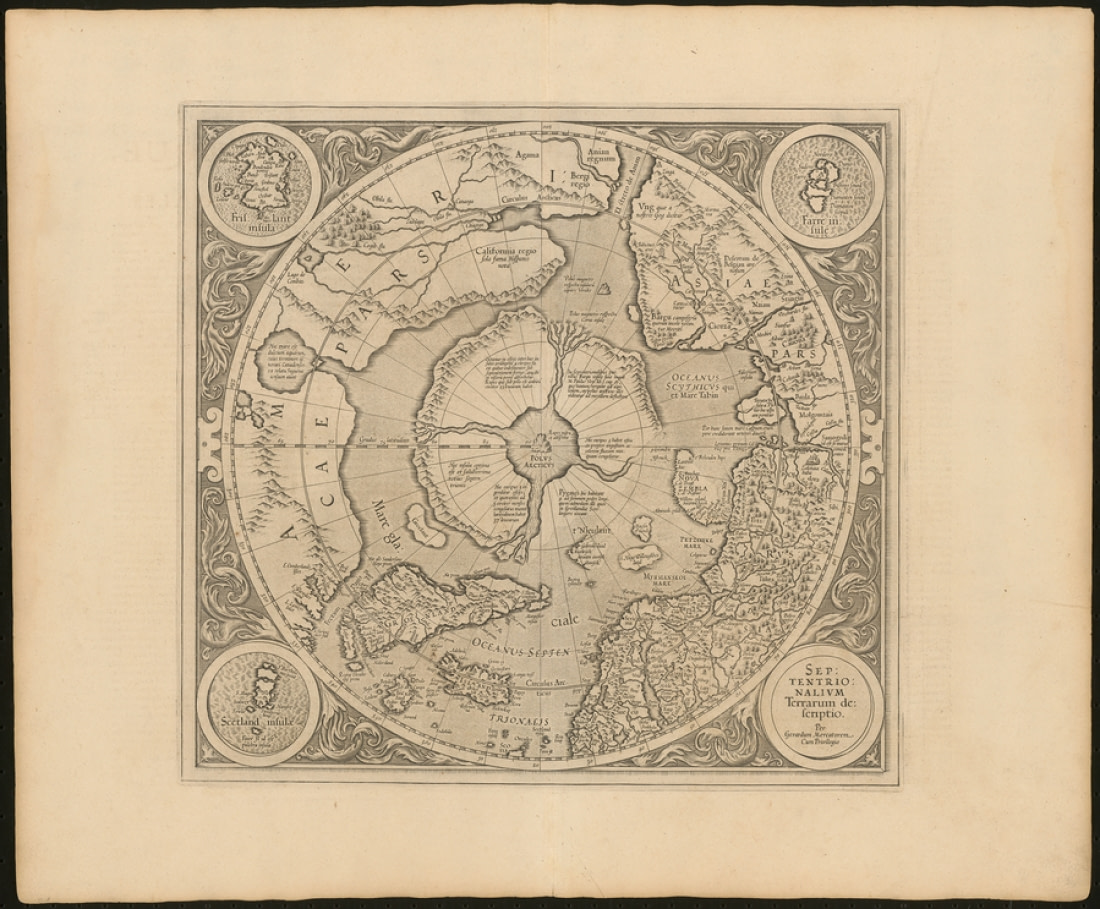

The Arctic was by no means least among the priorities of this age, and a number of key maps by largely Flemish and Dutch cartographers, especially Gerardus Mercator (1512 – 1594), illuminated areas of the Arctic previously unknown.

One of the chief concerns in the Arctic during this time was the discovery of a Northwest Passage, a trade waterway that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

John Cabot made an unsuccessful attempt in 1497, and Jacques Cartier found the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in 1564. Several British expeditions followed until 1609, led by explorers such as Martin Frobisher, John Davis, and Henry Hudson.

It wasn't until three hundred years later, in 1906, that Roald Amundsen completed the task, though the waterway he found was too long and shallow to be commercially viable.

During your next Arctic cruise, as you gaze over the peaks and glaciers or perhaps spot a polar bear trekking across the tundra, contemplate the long tradition of exploration that revealed these areas to the world, and relish the fact that you are able to experience some measure of that ancient adventure - but with showers and more predictable mealtimes.

Blog

Highlights from the First Arctic Voyage of Hondius

The Eight Albatrosses of Antarctica and the Sub-Antarctic

Solargraphy & Pin Hole photography in the Arctic

Life in the Polar Regions

The Classic Polar Cruise: Antarctic Peninsula Facts, Pics, and More

What’s so Special about East Spitsbergen?

Imperial Antarctica: the Snow Hill Emperor Penguins

A Diving Dream Fulfilled

Humpback Whales: the Stars of the Western Antarctic Peninsula

The Arctic Borderland of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard

The Pack Ice and Polar Bears of North Spitsbergen

10 Books and Films To Prepare for your Antarctica cruise

17 Reasons to Cruise the Falklands

10 Common Misconceptions About the Arctic

The Evolving Shipboard Eco-traveler

Cruising Solo: The Benefits of Single-Passenger Polar Travel

Diving in Antarctica: The Ultimate Underwater Experience

The Ultimate Traveler’s Guide to the Arctic and Antarctica

The Most Enchanting Antarctica Cruise Islands